On the 1st of April 2001, Sega officially stopped production of the Dreamcast. Despite an enourmous outpouring of creativity and future-thinking, gaming’s great stalwart cut off its home console lifeline in light of the commercial failure of the fight-or-flight console. Kat Bailey put together a fantastic retrospective featuring some interesting insider info from one of the team members of the Mizuguchi-led Sega AM3 group at the time, so we thought it was a good opportunity to reflect on Sega’s last hurrah.

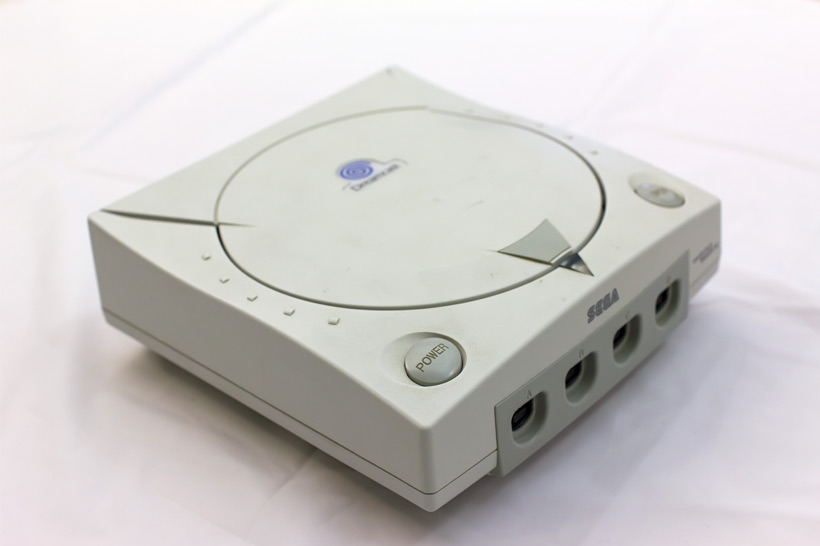

The Dreamcast was Sega’s proverbial crucible – the result of burning away the fractured international relationships between the Japanese and American offices, the barriers imposed on exploring creative ideas and leaving behind a purity that welcomed the future with open arms. The hardware was a reflection of traditional Japanese console development in that it kept the component supply chain amongst its Japanese business partners, but did so by eschewing custom processors and utilised off-the-shelf components, a decision that echoed in the use of Intel/Nvidia and PowerPC/ATi architecture in the Xbox and Gamecube respectively. It was the first home console to natively run at resolutions beyond standard definition, capable of outputting 480p in 4:3 and 16:9 aspect ratios via 31k RGBS (aka VGA), and the first to introduce a storage medium that extended the CD-ROM format’s storage woes. The inclusion of a modem in every console meant online play could be implemented with strong returns on investment, something the Xbox would leverage through its inclusion of a network socket in every machine. Oh, and it was also the first home console to embed a display in the controller.

For PAL users, it introduced a critical feature – the hardware was geared up to allow the end-user to set their refresh rate when booting a game and built in the chroma encoding to ensure PAL60 was good to go out of the box without requiring internally modifying the console. It also meant it reduced the need to import titles from US and Japan to satisfy a refresh rate modification, an issue that reared its ugly head when forcing PAL titles to 60hz on previous generations of consoles. While the PlayStation had the capability to switch refresh rates in software, developers were not authorised to use it and the console required modification to the mainboard to ensure the colour signal output from the video encoder was valid. This meant the era of PAL games running with borders that distorted the picture and the 17.5% slowdown inherent to poor conversions were a thing of the past, at least for the developers that took advantage of the feature (which were surprisingly many). This one feature in many ways was the first step technologically to break down the international barriers for game development so PAL gamers could enjoy their games in the way the developer’s intended, a situation we’re finally in with the advent of HD gaming and the standards adopted around the world as a result.

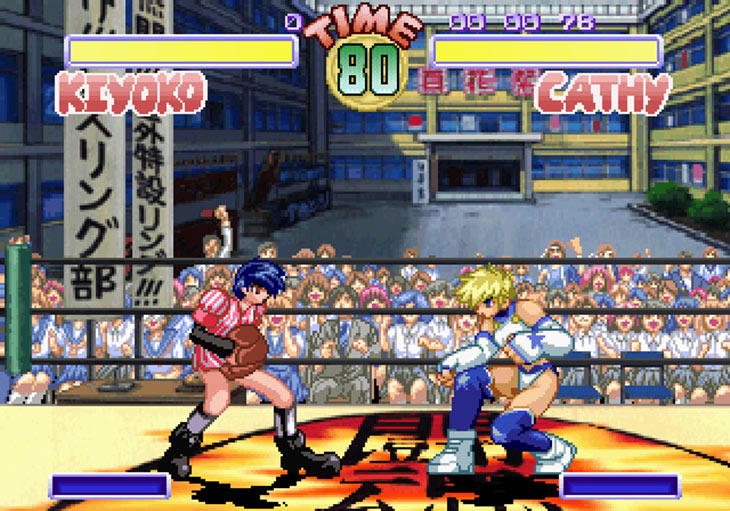

For me, the Dreamcast will be fondly remembered for its sheer energy and resilience. Sega fans had a machine that held its head high over the course of its short lifespan with some amazing single- and multiplayer titles. Co-founder Inferno and I spent many, many nights up late with my brothers or friends cranking through 4-player titles like Dead or Alive 2, Virtua Tennis, Quake 3, Powerstone 2, Unreal Tournament, Gauntlet Legends, Chu Chu Rocket and Armada. As big fighting game fans, we were catered for there as well – Capcom vs SNK, Marvel vs Capcom, King of Fighters ’99 Evolution, Rival Schools 2, Virtua Fighter 3, Street Fighter 3: Third Strike and Guilty Gear X were regular picks. Then there were the amazing arcade conversions in the form of Crazy Taxi, House of the Dead 2 and Confidential Mission.

Beyond those there were many other amazing titles to kick back and play solo. Rieko Kodama returned to her RPG roots by bringing the spirit of the 16-bit Phantasy Star games to the under-appreciated Skies of Arcadia, while Game Arts introduced a dramatically revamped sequel to the cult Saturn and PlayStation hit Grandia. Sword of the Berserk was short but demonstrated an impressive ability to tell a focused story amongst some capable visuals. Sonic Team blew our minds with the Sonic Adventure titles, even if they haven’t aged well, then did the impossible by bringing us Phantasy Star Online, the first console MMORPG. Sega’s internal studios pioneered cel shading with the visually arresting and aurally stunning Jet Set Radio, and Genki would create the template for my favourite racing series with the release of the Shutoku Battle games. Cult hit Sakura Taisen upped the production values in creating a fantastic iterative transformation of the beloved Saturn titles, with the systems introduced in the strategy RPG game evident in one of my favourite games of the last generation, Valkyria Chronicles.

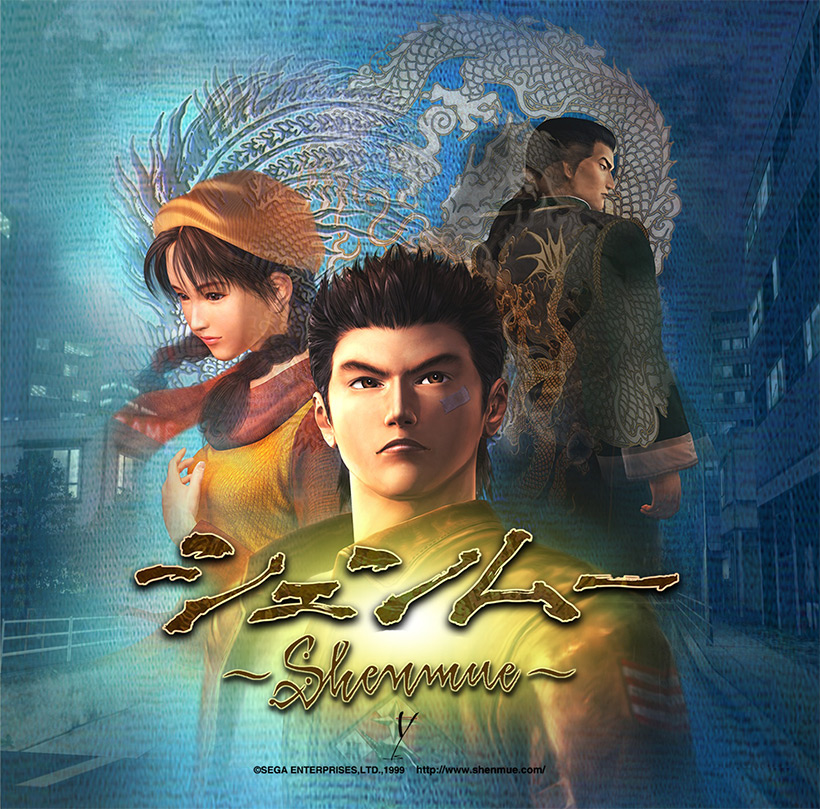

Then there’s Shenmue, a series so divisive but so ardently loved that it went and broke the Kickstarter website before smashing all previous funding records on the site for video games. The hours upon hours spent with the game’s endearingly awkward protagonist in Japan, Hong Kong and mainland China are amongst my most treasured gaming memories. It’s hard to explain or convey the experience of playing such an immersive and technically accomplished game at the time, especially when you consider that the original Shenmue title will be 20 years old in a few years!

The other bonus of the Dreamcast’s rise to market was that it opened up the official Australian Dreamcast forums, where co-founder Inferno and I stumbled across long-time contributor (and all-around dude) Sauceman before we all moved over to the Madman forums where we met more people who are also writing for Anime Inferno!

The Sega Dreamcast – a gaming pioneer, the tremendous fall of the old guard, a supernova of creativity and the catalyst that in many ways put together a group of nerdy otaku who are still writing about gaming and anime 15 years later on this website.

The Sega Dreamcast – to be this good takes ages.