Akira is one of the most celebrated anime releases of all time, and for good reason. The combination of stunning hand-drawn animation, incredible original soundtrack and harrowingly raw sci-fi narrative pushed across cultural divides and delivered considerable commercial success. With a native 4K digitally mastered print under their belt, it’s time to see how well Otomo’s visionary title stacks up with ultra high definition shinies in tow.

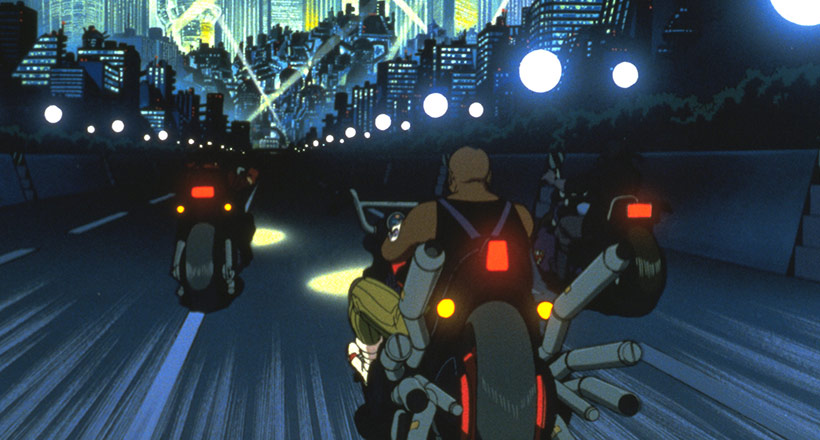

It’s hard to eloquently provide a written synopsis for Akira because there are so many threads scattered throughout this 2-hour animated masterpiece. On the surface though, the film adaptation of Akira focuses on the relationship and circumstances around Tetsuo and Kaneda, two high schoolers caught up in the gritty underground motorcycle hooligan scene in the not so distant future (or is it now the past? Hmmm). As orphans raised amongst the rubble of Neo Tokyo following World War 3 they typify the juvenile delinquents of the future as seen through the lens of the mid-80s.

Following a run-in with the military Tetsuo finds himself in a controlled facility where his potential for psychic enhancement is doggedly pursued to try and harness the next level in human evolution and the secret to revolutionise warfare. Things get weird when Tetsuo’s potential begins to run out of control and triggers a series of surreal and violent events culminating in the potential return of a god-like super power that could threaten the future of Neo Tokyo.

Akira was monumentally influential at the time, and in turn was heavily influenced by some of the great cyberpunk sci-fi productions that proceeded it, most notably Blade Runner. The film squeezes a huge amount of content into its 2-hour runtime, an achievement in itself given the manga hadn’t been finished at the time but had been running since 1982.

In some respects the insane level of density reflects a common challenge in the golden age of anime where the bubble economy fuelled amazing theatrical and direct to video animation to a sector more at home with extended, serialised narratives in manga and TV anime. Sometimes it works incredibly well (see Project A-Ko and Wicked City), but it often resulted in productions that were well-intentioned and gorgeously animated but didn’t quite bring it together (like Megazone 23).

In addition to its influence on Hollywood (The Matrix), anime (Ghost in the Shell, Human Lost) and western animation produced overseas (Batman Beyond), it also acted as the first major release that brought anime to the overseas markets. It featured limited theatrical runs in arthouse theatres around the world – even Adelaide managed to secure itself a theatrical run in the early 90s!

The infamous Streamline Pictures secured the English localisation and subsequent distribution, which in turn lead to the founding of Manga Entertainment on the back of its huge commercial success. In turn, Manga Entertainment became established in Australia and partnered with Siren Entertainment to manage local distribution in the first wave of anime that hit Australian video stores. If we’re chasing breadcrumbs, in many ways Akira is the genesis of the local anime scene.

It cannot be understated how foundational Akira is to Western anime fandom and how it successfully challenged the entrenched mindset that animation was only for kids and family viewing. Matt Schley, reflecting on the film’s 30th anniversary for the Japan Times, notes that Otomo’s work managed the unusual juggling act of providing critical discourse on Japan’s post-nuclear societal journey in a way that could be enjoyed on many levels and whose production style made it the perfect way to open up anime to a Western audience to have them reconsider what stories could be told in a feature length cartoon.

Akira succeeds because it is not just a case of novelty triggering a love for the production – the at-times overwhelming narrative is heavily codified. There’s the oft-explored parallels between the opening scene and the experiences in Nagasaki and Hiroshima during World War 2, the riots and political corruption echoes the post-occupation political movements and persistent issues in Japan’s socio-political structures. Themes of disenfranchised and neglected youth, interesting incorporation of the infamous bousouzoku gangs in the 80s, the dangers of fuelling scientific endeavour through militaristic frameworks and the development of child soldiers are all in there and ready for consumption and reflection.

Foundational works in Western discourse on anime, such as Susan J Napier’s Anime: From Akira to Princess Mononoke provided a great opportunity to apply film studies specific to anime, a novelty at the time of publication which has risen in prominence in academic discourse (many of the arguments of which are discussed in this piece by ees on The Artifice). Certainly as an undergraduate 20 years ago it was mind-blowing to see anime, often considered a form of pulp entertainment, elevated to the kind of discussion emerging in critical literature at the time. It encouraged myself (and many others) to think more broadly about the animation we were consuming to explore the author’s intents much as you’re often trained to do in other forms of literature or creative works. Such a journey in many ways was made possible because Akira provided such a dramatic opportunity for anime to head to the West.

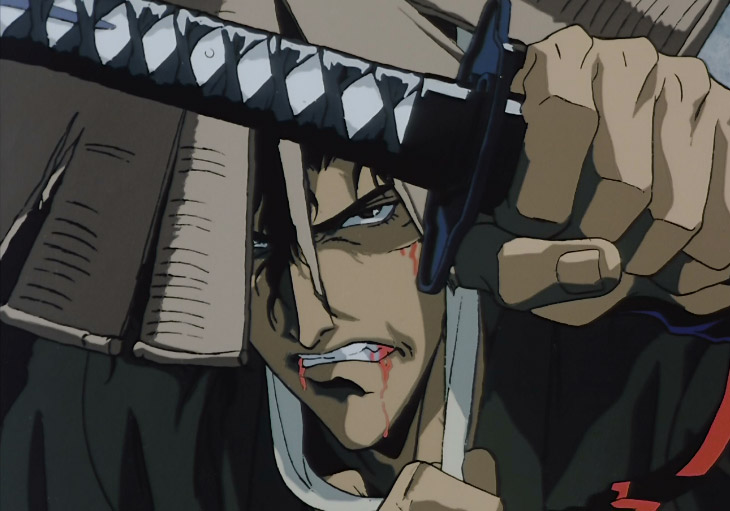

All of these themes and issues interfile within a series of excellent visual set pieces and gorgeous character designs that do a great job of translating Otomo’s iconic art from the manga into animation. Unusually for anime, fully lip-sync’d voice acting and a surreal soundtrack creates plenty of areas to sink your brain in and enjoy. Akira’s production was infamously hyper-intensive and featured extraordinary volumes of animated cels for its running time. Optical and early computer-generated CGI look fantastic, and the painted architecture is sumptuous.

The discussion of Akira’s production values is a perfect segue to talk about what makes this a unique release. Fully rescanned and remastered at native 4K from the original masters, the level of detail shown off is impressive. I lost count of the number of times I just sat back and soaked everything in. I recall having the same feeling each time I’ve enjoyed the leap across formats – the R4 DVD release featured a fantastic SD master with excellent sound, the local Blu-Ray release absolutely popped with a great 24p transfer and the lossless DTS soundtracks pushed the envelope compared to the Dolby Digital mixes of old.

There are some oddities though. Up close the digital noise reduction on the 4K transfer often muddies finer details, possibly with the intention of trying to make the animation production echo more recent digital production and deal with the grain inherent in the original film. At normal viewing distances I don’t think you’ll notice, but it would have been nice to see more of the beautiful, if slightly less refined, linework on the animation. In those scenes where the print was probably in super clean condition this smacks you right in the eyeballs – when Takashi freaks out when his rescuer is taken out, the detail in the animation during his psychic breakdown looks amazing. This contrasts with the wider shots during the bike race at the start of the film where those murky shades must have suffered a bit more from film grain and were denoised to suit.

Audio’s another oddity, though part of me feels Akira’s audio has always been a bit odd over the myriad of releases during its lifecycle. All three tracks – original dub, 2001 dub and Japanese – are downsampled 48khz Dolby TrueHD lossless tracks. While this makes sense for the original English dub (which is a great bonus for those of us who want to stroll down memory lane), the absence of the 96khz English 5.1 track from the 2009 Blu-Ray release, the 192khz ultra high definition Japanese audio track from the 2009 Blu-Ray or the newly remastered 192khz audio from the Japanese UHD release is disappointing. The included Blu-Ray pressing though, which is a new pressing distinct from the 2009 Madman release, features the 96khz English track and what looks to be the newest 192khz Japanese audio (based purely on bitstream extracts as the files sizes are different).

We reached out to Madman as part of this review and they’ve confirmed the Australian release mirrors both the HDR-enabled US and UK releases, which have noted the same inconsistency in audio tracks. While there’s no official explanation for the changes, this may suggest video encoding was prioritised ahead of audio (an investigation on the US release noted almost the entire scope of the UHD disc is full, so the 192khz Japanese audio track would have bitten into the video encode) or perhaps there were licensing restrictions to reduce the impact of reverse-importation into the local Japanese market.

Or it could be neither – this is pure speculation.

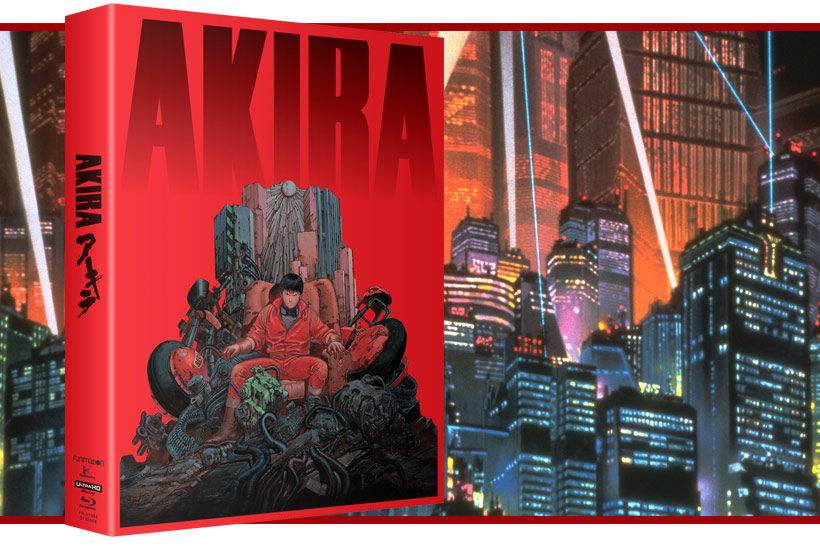

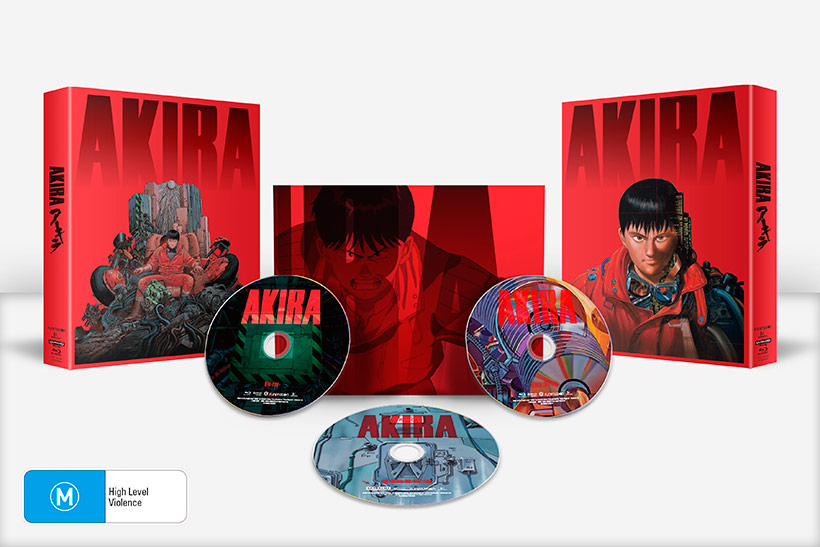

To complement this release, Madman have included a swag of bonuses. In addition to the UHD disc we have a new Blu-Ray pressing (handy for those who haven’t upgraded their playback equipment) and a dedicated disc with bonus features. There’s also a full-colour companion booklet packed with gorgeous prints, commentary and interviews about Akira. All of this is housed in a neat box set featuring thick, bold cardboard stock printed at a high quality. Where the previous DVD and Blu-Ray releases felt a little utilitarian (though we need to exclude the previous Blu-Ray + LP bundle which was pretty awesome), this latest release strikes a nice compromise in terms of shelf space and quality content.

Despite the nerdy nitpicking, there’s very little not to recommend for the Australian 4K UHD Blu-Ray release of Akira. The movie is amazing, the transfer benefits from the higher resolution, colour depth and bitrate, while the extra materials are incredibly comprehensive. If we could get the 192khz Japanese audio track in here this would be on the cusp of a grand slam of a release, but as it is this remains essential viewing for all anime fans.

A review copy was provided by Madman Entertainment to the author for the purpose of this review.